Against the Grain

The standard career path often tells us to study hard in school, focus on a particular subject, and work our way up the ranks in that specific field. Many engineers would love to just tinker their whole life, but eventually companies want someone who can transition into the management side of the business. Yet even some of the most desirable managers have not strayed too far from their main industry to become a “jack of all trades” in a diverse set of fields. Maybe this idea is changing, but most job listings seem to want so many years experience in this or that particular thing, without much wiggle room for atypical candidates, even if that person may be completely qualified to do the job with just a quick knack to learning.

In college, I pursued a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering with a focus on analog electronics and signal processing. Later in the military, I would take on a different task of learning how to manage systems-level engineering projects rather than focusing as much on technical design. Although much of my background was in electronics, I was collaborating with technical teams all across the engineering spectrum, needing to at least be able to understand little bits here and there of various subjects. I certainly enjoyed the ability to move around and dabble in different departments, but within a year my thoughts on life would steer me on a completely different path. I was discovering new ideas and philosophy, which surprisingly at the same time, one of my good college friends was also questioning the direction his life was going—deciding to take a full year off to go backpacking in East Asia. The idea of travel felt like a dream and who wouldn’t want to know what it was like to be free from what everyone says you should be doing—to live life completely on your own terms, “for each day to have a new and different sun.”

I would soon go on my own traveling adventure, but after I returned my mind was still all over the place. I had so many ideas, so many things I wanted to learn, and so many things to do. A friend of mine found work in tutoring, so I thought maybe I would use my past experience in the Air Force Study Buddies program to help kids struggling with math and science. My love for nature and a desire to simplify my life pushed me on a very unique path in conservation and horticulture. Each idea was an experiment with no planned destination; my confidence was not always present, but I felt good in the fact that I was really trying to challenge myself to seek something I truly wanted. “I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.”

Early Gardens, Early Beginnings

In 2012, I had my first real taste of working with plants. I had always had an interest in nature: watching wildlife documentaries on Animal Planet and Discovery Channel; helping my grandparents do small tasks with their backyard garden; and a moment where I thought I might even study in the agricultural field at Penn State. While working at Hanscom Air Force Base, I rented an apartment close to the city, being convinced by the landlord that this was the place to be for young people of my age. I was definitely looking forward to exploring the rich history of Boston, but also getting out and socializing with other young people—I expected Boston to be like a larger version of my time at Penn State. I never really thought I would be investing so much of my time starting a garden in the backyard. My neighbors had recently brought home some trays of vegetables that would sit out there for weeks, and I wanted to find a good home where they could grow into healthy full plants. I found a plot where the grass was dying—I would later understand due to lack of sun—and dug out a nice trench, refilling the area with fresh garden soil—I didn’t wan’t to take any chances with the possibilities of contaminants. I then plugged away at the dirt, plopping each plant into the ground with what I guessed to be enough space for them to grow. For such a shady area, it was a surprise that anything even survived, but with some minor difficulties, I had quite the harvest.

As I moved around the Boston area, I would continue my green thumb tradition. Although I would no longer have any physical ground to plant in, I started to create container herb gardens wherever I could find the space. It was a lot easier than vegetables, but it still had that same satisfaction of working directly in the soil. I had fresh herbs at my fingertips, which I barely used, but just the activity of watching something you planted fully mature was satisfying enough for me. I began to discover that nature’s beauty is more than just what it can do for us—our understanding often determined by the familiarity of agriculture and growing “pretty” ornamental plants—but the complexity in which our relationship is developed. Looking back, I never thought these early days would plant a seed that would soon grow into a full passion of understanding the innate processes of the natural world.

Seeking Solitude

Education may prepare you for the technical qualifications of the job, but it doesn’t teach you how to be successful in the workplace. Also, the structure and instruction provided falls apart in the real world—there’s no golden handbook for how to live life. Over time, everything in the city just felt cold and distant: people would pass by you every day without looking in your direction; neighbors would disappear for months as you barely got to know their names; work throws you in an office and expects you to figure it out. It was nothing like being on a campus of thousands of motivated students carving out the future of their lives. There were no guidance counselors, teachers you could go to for help, or shared activities that made bonding so easy—it was all up to you and you alone, and that is a very scary realization.

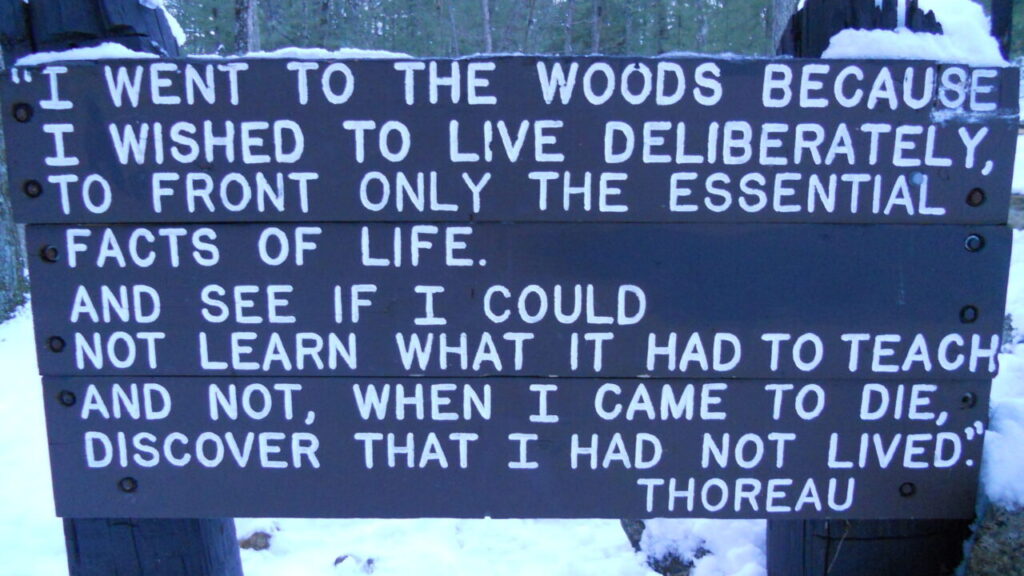

One late evening, I was browsing through Netflix and the title Into the Wild came onto the screen. There was something mysterious and alluring, pulling me in under its spell. The music, visuals, story: everything about the film shook my body and resonated throughout my being. It was like all the questions I was seeking answers to were passing right before my eyes: the desire for adventure; the yearning to accomplish great things; and “to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life.”

Christopher McCandless was a madman—a rebel against the complacency that often exists in this confusing world. His parents held a standard conservative view of life: they encouraged him to attend university and hoped he would go to law school; they felt attaining a certain amount of wealth would portray a certain status among people; and accordingly provided Chris with a very privileged upbringing. Just a few days before he disappeared on his great adventure, his parents inform him that they would like to get him a new car—to get him out of the old yellow Datsun that he had been driving since high school. “I don’t need a new car. I don’t want a new car. I don’t want any thing–these things, things, things.” Soon after, he donated all his savings to charity, destroyed his ID, and cut all his credit cards. He disappeared from everyone he had known without a trace, taking on a new identity that would express his disregard for material pleasures and passion for adventure—Alexander Supertramp.

“Two years he walks the earth. Ultimate freedom. An extremist. An aesthetic voyager whose home is the road.” Chris traveled extensively throughout the United States before making his final journey to Alaska. He came close to death several times but through will and perseverance he braved through dangerous obstacles. His eccentric spirit made a considerable impression on all the people he met: Wayne Westerberg gave him a place to stay and allowed him to work backbreaking jobs both in Montana and South Dakota; Jan Burress and her boyfriend, fellow “rubber tramps”, related to the fire in his heart but worried about his reckless behavior, seeing glimpses of an estranged son she once held dear; and Ron Franz who lost his own wife and kids in a horrible accident begged to adopt him as his own. One can only guess if it was McCandless himself or the books he read and brought along in the journey that helped him become this charismatic personality.

Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Jack London’s Call of the Wild, and Leo Tolstoy’s works surely had the greatest influence on his personal philosophy: the theme of restlessness with modern society and a yearning for a more fulfilling life. Primarily, he connects with the idea of living a simple life, rejecting civilization and existing only on the bare necessities. While both Thoreau and McCandless seem to be seeking isolation in their spiritual journey, it’s interesting to note they always find great pleasure in the experiences they have with other people. When Thoreau was living by himself in the cabin at Walden, he would often take in visitors or speak to passengers passing by on the Fitchburg train. While Chris certainly felt a disconnect from society and people, he makes an extremely positive impact on those he meets on the road. Alaska wasn’t about being isolated from the world, but facing great challenges with just his own hands and feet—enjoying the beauty of being completely self-reliant and connecting with a most primitive state of man that industrial society seems to have lost. Unfortunately he realizes in his final moments the importance of this need for human connection, inscribing in Leo Tolstoy’s Family Happiness that “Happiness (is) only real when shared.”

New Tools

Into the Wild was the spark that ignited a burning flame to seek out new knowledge and learn more about what history had to say in regards to living your best life. I first began to research the books that Chris took with him and the people he referenced in his journal during his journey. Starting with Walden, the powerful words on the page described a world that felt so close to home, capturing the beauty of nature and the essence of life. The industrial world was cold and dirty: men toiling like big machines in a place with no meaning. The true antidote to all this was to return to our roots, to recognize the simple beauty in nature. In the winter, I went to visit Walden Pond. I was completely alone in a sea of white, barely a sound from both man or beast. “The snow lying deep on the earth dotted with young pines, and the very slope of the hill seemed to say, Forward!” As I stood there at the cabin site, I tried to place myself in his shoes. I was visualizing the scenes from the book, trying to connect with the feeling of living here for two long years. In subsequent trips, I would visit the Emerson house just a few miles up the road, walk past homes where Louisa May Alcott and Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote their famous novels, and visit the burial ground of Concord’s most famous. Each visit would be its own pilgrimage, carving a special place in my heart for the love of history, literature, and philosophy.

What does it mean to live a happy life? This was the burning question on my mind during this time. I looked to ancient Greek philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle: urging people to seek knowledge and wisdom, knowing oneself, and asking questions about the world around them. The Stoics like Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius practiced a sort of indifference toward the chaos of the world, and strived towards virtues that lie in accordance with the “natural order” of things. In the 1960s, many people looked to the East for similar ideas of obtaining serenity and peace in a troubled world. Books such as Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Alan Watt’s famous lectures began to popularize Chinese and Japanese philosophy in the Western world. People revived the writings of Hermann Hesse, who borrowed ideas from both Hinduism and Buddhism—attacking the need for one to change the world and offering a sense of acceptance of the state of things. He negates the mind’s illusion of seeking to attain something but rather to accept one’s own imperfection and the world around them. Not only do these imperfections exist, but Hesse often asserts that they are a necessary and crucial part of life, an idea that is very difficult for most people to come to terms with. In the past few years, figures like Ekhart Tolle would synchronize these teachings about the mind and even celebrities like Jim Carrey and Russell Brand would gain prominence as they made radical changes in themselves: focusing on the mind rather than the external world as being a sole source of human dissatisfaction. Yet, the tragedy of authors like David Foster Wallace remind us that this very challenge of dealing with the mind is still difficult even in those who are actively working to recognize its behaviors. I felt that I could sit and ponder these thoughts for ages or discuss ideas with those also trying to find out the big answers to life, but no amount of thinking can pass the test of lived experience. I had a yearning to get out there and I needed to discover my own answers to life in the journey that lie ahead.

Catch the Sun

April 25, 2016, I was sitting on an airplane from Boston to Iceland: a one-way ticket to the unknown. I sold what I could and donated the rest: my vehicle, guitars, books—anything that I couldn’t fit in a backpack had to go. The only thing I had left was a small Priority Mail box that I sent back to my parents; my pack was filled with minimal clothes, small toiletries, an iPad, a couple books (Thomas More’s Utopia and Descarte’s Meditations), and an old school CD player. I remember sitting on the floor in an empty room, saying my final goodbyes to friends and loved ones. Although we would be able to communicate through email and the occasional Skype, I knew these moments were important, as it would be a while before we truly felt connected again.

We set out in the late evening; it’s about 6 hours to Keflavík Airport and another 5 hour delay with the time zone shift. I barely slept; after a few hours the sun started to peek through the little window, stimulating the already restless feeling I had in my bones. I was ready to arrive: to finally descend over the dark volcanic rock of Reykjanes peninsula and to feel the chilly sea winds rush through my body. Before the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, the island was a relatively quiet place. The most that you would see in the newspapers is a stray sheep that escaped from a local farm or rumors of the next volcanic tremor. Now that more and more people are coming to Iceland each year, much of the focus has been on the impact of tourism on natural spaces and the pressure on search and rescue teams from naive visitors. When I finally arrived, it was about 5am and the place was practically dead—even surrounding towns were shut down until about 9 o’clock—it was a surreal feeling. As I stepped out the doors, I was greeted by the cold morning air. My eyes glimmered with a mission of reaching town. There was no bus going to Keflavík—the only thing available is the regular Flybus that goes between the small capital city of Reykjavík and the airport—so I had no other choice but to hoof it. As I journeyed forward, the voice of Chris McCandless was but a faint whisper on the wind, gently reminding me that “I (too) now walk into the wild.”