Big Math Guy

I walked into a classroom half full of kids, and in the front of the class I heard a student make a sarcastic remark about “how much fun math is”. He turned and looked at me, and the first thing out of his mouth was “Mr. Reihner, you a big math guy?” I didn’t know what to say. Was the question asking if I was good at math or if I enjoyed the subject? Neither answer I had prepared would be the right one, as it had been years since I even touched a math problem, and over time much of my booming interest in math from my engineering days had fizzled out. Recently, my passions took on a more science and design driven path: working outside digging in the dirt and learning about the ecology of native plants. When it became clear that my current situation would have very little growth opportunities, I was at another crossroads in my career journey. I needed something that would be challenging but also help me gain a financial foothold so that I could move toward bigger opportunities in life. I wanted to have money that I could potentially invest in my education or put towards starting my own business. I looked over at the student and gave him an honest answer. If I was gonna have any chance of winning him over, there was no point in trying to sugarcoat things. I wasn’t going to be your typical career teacher. I had not yet figured out my relationship to math and most of all I had no idea where this whole experience was going.

Throughout my studies, I always had a desire to help my friends and classmates who were struggling in math. I remember my senior year of high school, our calculus teacher would make us read the book and do some homework problems before he taught the lesson. This more independent working style was a big shock to some of us, and many students had trouble keeping up with the demand of the class. It was certainly difficult, but I would just go home at night and sit with it until things started coming together. Students knew me as the highest achiever in that class, but I stayed humble about it, and whenever I finished my work, I would go over and see if anyone needed any help. Sometimes I was that annoying kid that would try to clarify things over the teacher when my classmates got stuck, but for the most part I had good intentions. I just wanted to see everyone succeed.

In college, math was a whole other beast. Imagine getting a 103% in senior calculus to barely crawling out with a C in most undergraduate courses. The material was just so much harder and the classes were very fast paced. You couldn’t just show up to class and rely on the teacher to prepare you for success. It required a lot of independent research, collaboration with students, and tactful gumption to be able to do the homework and prepare for exams. You were blessed if you could find one person who knew what they were doing and were willing to help you study. Many times I would pair up with someone to do homework or prepare for exams, while other times—by divine grace—I understood enough of the class to actually become the tutor myself. One of my best math classes was Ordinary Differential Equations, often touted as one of the most difficult math classes for engineers. My teacher wasn’t always the easiest to understand, but she laid out a lot of things in steps and solving these problems felt a lot like organizing little puzzles. You had blueprints for different types of problems and if you could get them into that form, it was smooth sailing. Before big tests, I would help my friend who had a very different teacher from me and would guide him through the steps I had learned from class. Not only did it help me review the subject, but it reinforced concepts and tested me on how much I really knew. I found throughout life that talking through ideas is an especially effective way to learn and flesh out different concepts. Sometimes things get stuck in your head but having these dialogues provides a roadmap for all these jumbled thoughts.

When I got into the military, the most disappointing part of the job was I barely used any of this math or engineering knowledge at all. All those long nights torturing myself to understand these complex problems was all for nothing if I would never use it again. The job focused mostly on developing my leadership and program management skills, and I was just the one overseeing all the people who were doing the cool stuff. During my whole military career, I only have one bullet on my resume that says I made important calculations to fix a critical antenna issue. In reality, all I did was just watch my boss write out a simple formula and try to remember any bit of information from my electromagnetics course to figure out how it was derived. I can’t say the whole experience was entirely negative though. I met some really great people and we had some good laughs in even the most stressful situations. I learned great skills that I continue to use to this day, but I just missed being away from the part of engineering that I had always loved. In school, I had multiple projects where I had to pour through hours of books and online articles to understand new topics and develop initial prototypes to experiment with. I tinkered around in the lab, building and simulating various setups to see which model best met the specific design requirements. I spent whole semesters just working on a couple projects, but felt invigorated each day taking part in this process. Once you finish your final design, you look back at all the challenges you overcame and what you accomplished to get this far. With a sigh of relief, you feel a sense of completeness—your mind is at peace and your body fulfilled—until you get another spark of an idea and you end up doing the whole process all over again. As an engineer in the working world, I thought I would be doing much of the same stuff—creating, inventing, exploring—but for about 80% of the time I was drowning in a sea of documents, emails, and a never-ending stream of daily meetings. All of my college textbooks lay barren on the shelf, merely collecting dust from a memory slowly fading away. I wanted to bring them back to life, but I often sat staring at them not knowing what to do. Without school and the knowledge base of teachers and peers, it was difficult to explore project ideas and find ways to use this technical knowledge again. I needed to do something though, something other than this just to keep me sane.

Thankfully I met a colleague who oversaw a free tutoring program for children of military families. About once a week, young officers would dedicate about 1-2 hours for homework help and to review lesson materials. I was quickly paired up with a sophomore high school student who was struggling in Algebra II. He was such a good kid and his mom was always so involved and helpful in trying to get his grades up. She would often bring me snacks or meals as a way to make up for the fact she wasn’t paying anything for my help. Sitting with him those days, I didn’t just go straight into math homework. I tried getting to know him and build a connection, really wanting to understand his strengths and weaknesses and where he wanted to take his life. I understood that he would probably not remember or use much of what he learned in this class later in life, but at the very least he had a desire to pass. Each day I was almost learning on the fly. He would show me the homework that he was working on and sometimes I would need to reference his class notes to refresh myself on the material. Algebra II has some very specific and tricky subject areas that are easy to drift from memory when you haven’t used them consistently. I had only been a couple years out of college, but there’s a reason why math requires daily practice when you study it. I knew that one session a week wasn’t going to turn him into a math superstar, but along with the extra problems that he was doing at home, he was able to pick himself up from squeaking by with barely a D to getting a C in the class. Ultimately my presence didn’t really do much in regards to academics but the real benefit was fostering confidence with the subject and the personal relationship which made the process a little less painful.

In school, I was a straight A student. It’s not that I was particularly that bright, but I just loved the process of learning and wanted to know everything about the world. I felt excited each year to enter into a different grade with brand new classes and teachers—maybe explore a different part of the school that I had never been or even go to a brand new building entirely. While I did work hard, I found the process of finding success in school to be quite easy: follow the rules, listen to the teachers, and get good grades. During parent-teacher conferences, I was always praised for my academic achievements, even so far as one teacher saying that I could be president or cure cancer—a little much I think—but what teachers never really saw was that as a kid I had no real identity. As I progressed through life I continued doing what everyone else told me I should be doing, but none of it truly made me happy. The American Dream was just a big facade—do well in school, go to college, land a good paying job, and then you’ll be happy—and unfortunately everyone drank the Kool-Aid. For once in my life I just wanted to make my own decisions. I wanted to truly discover what the world had to offer outside of this mundane system. I wanted to take my own steps. After my time in the military I quit everything, sold all that I had besides what I could fit in a backpack, and took off on a real adventure into unknown and unexpected places.

Returning from a year of backpacking in Europe, I saw the world with new eyes. Although I was still trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, the world felt like it was ripe with opportunities. There was so much that could be done and yet, so much potential wasted by those who who were sitting up in office buildings trying to follow all the rules. I was perfectly fine with the simple life. I didn’t need to make all this money. I didn’t need to live in a big house with all these fancy gadgets. I could try out different things and just explore where life could take me. Maybe I could work in a bookstore or do some cashier job in a local restaurant. I could join a community action group to help improve the lives of those in the neighborhood. A friend who I was staying with for a short time gave me the idea of doing some math tutoring on the side. He was making good money utilizing an online website to find clients and only working a few hours a day. It seemed like a great way for me to have more flexibility around my schedule and actually get the chance to use my technical knowledge again. For once, I could actually feel like my degree meant something. I quickly signed up for an account and started working through SAT books and Khan Academy courses. I worked for months off and on trying to build up my math knowledge and reach out to clients, but I wasn’t hearing any response. I guess it made sense as to why many people decided to take the standard route. Forging your own path in life is not an easy road, but I was stubborn and unwilling to give up.

Over the last four years, I found myself working as a fine gardener for several companies. The idea of being a math tutor took a back seat as I was learning this new and exciting world of plants. I enjoyed the physical aspect of it and being able to work with my hands. Coming home dirty every day felt like an accomplishment—when you visited a property you often left with a finished project and directly saw the fruits of your labors. In a confusing turn of events, I unfortunately got laid off from my first job. It was a huge shock that came out of nowhere, but rather than sitting around and wallowing in sadness, I got out of bed and decided to take a trip to a place I had been wondering about for some time: Garden in the Woods. It was a sign that I often drove by on the highway but had no idea what it was. The visit was astounding! I walked the outside grounds and visited the garden center where you could purchase books on native plants and create your own botanical garden. Since my landlord had done nothing with the yard, I had all this open space where I started doing just that. The following year I ended up getting a job with this place as their main salesperson, where I learned skills that I took off to other companies who were more engaged directly out in the field. However, finding a company that specialized particularly in native plants was tough to come by and not having studied any landscape design limited my growth opportunities. Although I had all this knowledge and a unique background and skillset, most jobs I worked for did not take advantage of this. Each day I would just come in and do whatever grunt work that was necessary and go home. I was just a simple laborer but I desired to be more than that. If I really wanted to make something out of this, I’d have to do it on my own. I would need to build up to it first and in the meantime find some way to make money. The lingering thought of math creeped again back into my mind. I poured through listings from tutoring, specialized instruction, and temporary substituting roles until finally something stuck.

Back in January, I surprised my old college engineering friend with the news that I became a teacher. I told him that I was considering studying up on all my old college subjects again so that I could take the Fundamentals of Engineering certification.

“Do you think you’d teach physics or chemistry if they gave you the chance?” he asked.

“Sure, once I get the math stuff down I might just relearn my whole degree and take the FE out of pure spite.”

“Like to spite yourself? That almost sounds masochistic!”

I still haven’t figured out an explanation to this desire of mine, but college was such a disappointing experience. I went from having high school teachers who really strived to be good at their job and make sure that everyone succeeded to some classes with giant lecture halls upwards of 400 people. If you didn’t get the material during lecture, you better hope that you don’t have a class during your professor’s very limited office hours. Many of the professors were hired because of the research they do, not necessarily their teaching skills. Just because you are a master in your field doesn’t mean you have the ability to teach it. The worst part was when you could just tell that teachers weren’t at all invested in the quality of the class.

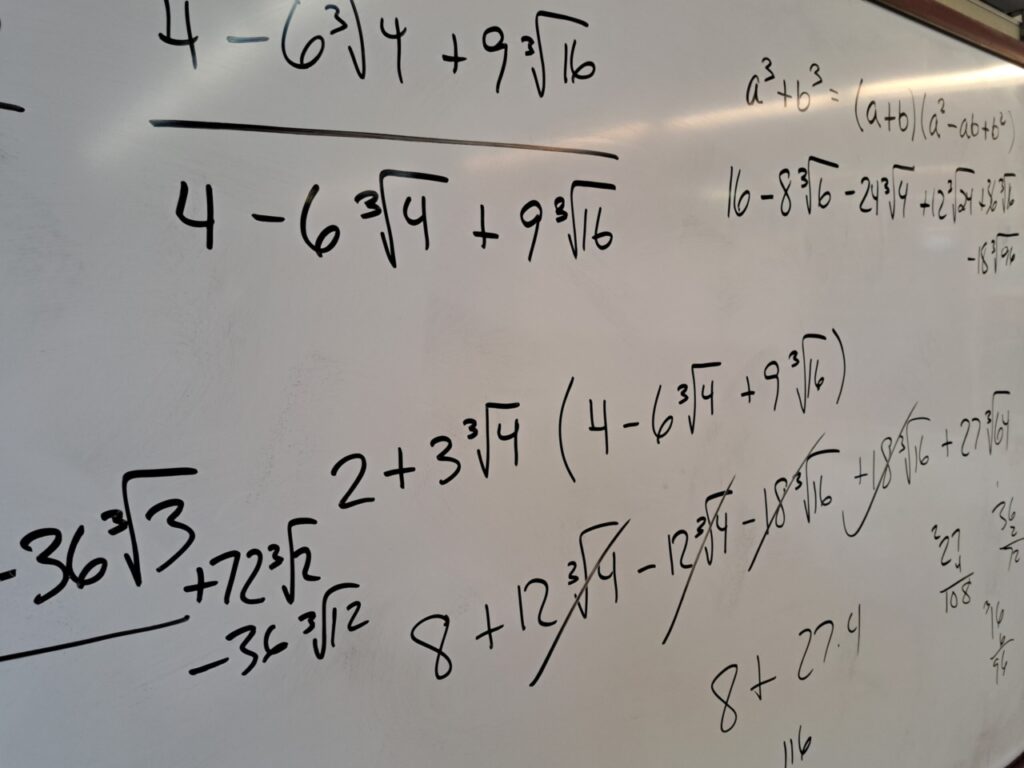

As a teacher, I’ve spent a lot of time and resources on just one lesson. I’ve purchased several textbooks with my own money so that I could have just the right material to deliver to the class. I’ve spent hours refreshing my knowledge and working out several examples from each of these books. Even when you think you have the perfect lesson plan, not every class is the same. You have to feel out the dynamic of the students and the classroom, constantly evolving your scheduling and presentation on a day to day basis. My smallest classrooms in college were about 30 people, and I can easily say that I struggle with a class of 20. Even in the smallest classes, this relationship didn’t really exist in college. When the professor would ask if anyone had any questions, nobody often had the courage to raise their hand because they were just as lost as everyone else. When they did, the conversation would often go on too long that it would be sidetracked to seeing the professor during office hours. I want to make up for all those disappointing experiences. I want to challenge my students and help them realize that college and the future ahead isn’t always going to be this easy, while at the same time giving them the best damn education that they truly deserve. No student should be left to fend for themselves, whether it be college or high school.

In the last days of the school year, a student asked me “What is it that you like about math?” With all the textbooks I had purchased and even going so far as to check out a math history book at the library, I was discovering the answer to this same question for myself. Learning about the development of mathematics and the lives of those who invested so much time in advancing these subjects, things started to make much more sense. This new language was no longer a robotic process or abstract science. You could see connections between real life problems and relationships interwoven within various fields of study. Many of the people who made great contributions to mathematics were also involved in other things. They were painters and poets. They looked to the stars and tried to map out unknown territories. They were philosophers with a love of wisdom and a yearning to understand how the world works. It was Pythagoras of Samos who theorized that the arche, or originating principle of nature, was formed by numbers. Math is all around us. It is a science, an art, a philosophy. The page is your canvas. The symbols the figures in which you paint. How could mathematics ever be boring when you are ultimately discovering the foundational principles of the universe.

The final day I looked out into an empty classroom and I thought back at my very first semester of teaching. It was a journey with its ups and down—students struggling to grasp the concepts or lacking motivation to put in the work that is needed. One week you felt like you made great progress and then the next completely lost. There were certainly moments where I wasn’t sure if I could do it anymore, but no matter the circumstances I couldn’t abandon these kids. While some teachers wouldn’t stop reminding you about the relief in the approaching end, once you got there, things felt bittersweet. You miss that constant interaction that you had with them—even the ones that drove you absolutely insane on a daily basis. You miss the stupid and silly things they do to get on your nerves. You miss the fact that they are moving on to another teacher and you will likely only see them in passing in the hallways. In a way it is like losing a friend, and you just hope that what you did made an impact in their lives and set them up for success in the future.